The town was small. Osage, Iowa. Todd McKinley was the fifth generation to grow up in the county 20 miles from Minnesota.

It was the kind of place where teachers taught kids to reach for the stars. Where parents, and grandparents and aunts and uncles told teenagers: “You can be anything you want to be.”

Teenage Todd wanted to be an astronaut. Yes. He would zoom into space in a shuttle. He would be one of the chosen few to explore unknown parts of the galaxy.

And Todd McKinley almost did.

He was as close as a person can get, whittled down to 100 people by NASA, as a finalist for the space program. When the last cuts were made in 1998, though, he didn’t land in the pool of 19.

But his dream is important, extremely important.

Because if McKinley, M.D., an orthopedic trauma surgeon at IU Health Methodist Hospital, hadn’t reached for the stars, he would have never been led to a career in medicine.

A career where he saves lives every single day.

**

The majority of what Dr. McKinley deals with are horrific cases. Car wrecks, motorcycle accidents, gunshots, someone jumping off a building, someone being run over by a car.

He’s not dealing with twisted legs and torn ligaments. He’s dealing with devastating and deadly injury.

“You get to do remarkable stuff every day and no two days are ever really the same,” he says. “There are literally hundreds, if not thousands, of remarkable cases a year.”

And, at the end of the day, in most cases, the end result is amazing.

“The best part of our job,” Dr. McKinley says, “is trying to help somebody back into their life who had it ripped out from underneath them.”

***

Growing up in Osage, McKinley’s father was an attorney and his mom stayed home with him and his two siblings.

Growing up in Osage, McKinley’s father was an attorney and his mom stayed home with him and his two siblings.

Dr. McKinley participated in a lot of sports as a kid, but he excelled in wrestling. Competing in the 155-pound weight class, Dr. McKinley was a two-time high school state winner, placing third and fifth.

When it came time for college, he went for that astronaut dream.

At the University of Minnesota, he graduated with a degree in aerospace engineering.

Dr. McKinley then took a job doing research and design of stealth aircraft at a St. Louis company. All the while, though, those dreams of being an astronaut lingered.

How could he get into space? Dr. McKinley noticed a lot of people selected into the space program had a mix of engineering and a medical background.

“I’ve got to figure out how to get into medical school,” he says. “I literally have no clue.”

So, Dr. McKinley went to Minneapolis and marched into the office of the dean of Minnesota’s medical school with one burning question: “How do I get in?”

***

The dean told Dr. McKinley there was an admission test a month later. The problem was, Dr. McKinley hadn’t taken half of the classes needed to pass. He hadn’t set his sights on a medical career until then.

“I figured I’d give it a shot anyway,” he says.

Dr. McKinley went out and bought the monstrous textbooks — a yellow one on organic chemistry, a red one on human physiology.

And he read and studied and pored over those textbooks. Every night, after a long day at his engineering job, Dr. McKinley taught himself.

And he passed that test.

In medical school, Dr. McKinley’s favorite part was critical care. But in the fall of his senior year, after two weeks in orthopedics, he fell in love with the field.

He can’t describe exactly why he was drawn in. There wasn’t a certain case or patient, but the people around him seemed really happy.

The problem was there weren’t many senior orthopedic rotations left. The medical school dean pulled some strings and found a rotation at the Mayo Clinic.

After finishing a month later, Mayo offered him a spot. But Dr. McKinley was interviewing other places, including the University of California, Davis. Within five minutes of being there, Dr. McKinley knew this was his place.

He moved to California in 1992, completing his ortho residency, a 5-year program. He then spent another year in a research fellowship at UC Davis before heading to Baltimore for a fellowship in orthopedic trauma.

It was during that time in 1998 that Dr. McKinley found out he hadn’t made the space program. His dreams of being an astronaut on the back burner, he took at job in 1999 at the University of Iowa. There, he also served as the school’s wrestling team physician.

He traveled to meets. He relived his own days of competition and he loved it.

“I’m not a sports doctor,” Dr. McKinley says. “But I loved wrestling so much.”

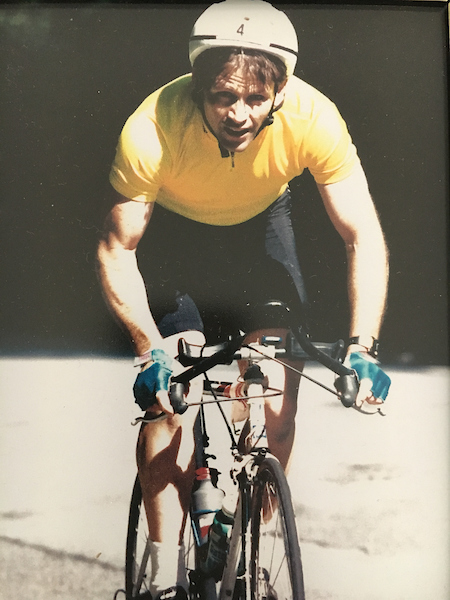

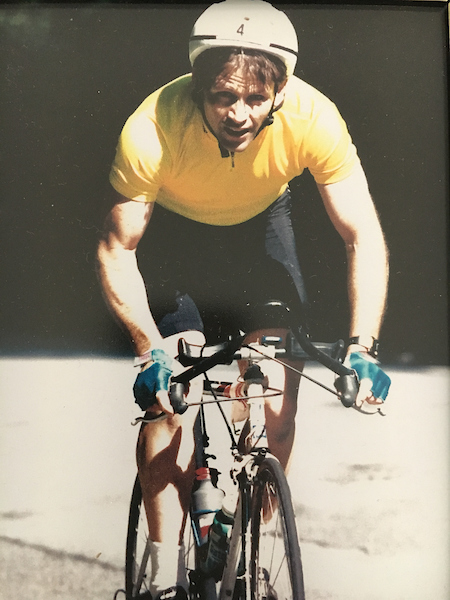

He had always loved competition. In fact, Dr. McKinley had been an Ironman.

***

While in undergrad at Minnesota, there was a triathlon in the Twin Cities. Dr. McKinley had never really swam a stroke in his life, but he decided to give the competition a try.

While in undergrad at Minnesota, there was a triathlon in the Twin Cities. Dr. McKinley had never really swam a stroke in his life, but he decided to give the competition a try.

“I almost drowned,” he says. “I struggled out of the water and hopped on the bike and drove 15 miles. Halfway through the race, I realized I really liked it.”

Dr. McKinley competed in more races, met more people and, before he knew it, had completed nearly 60 triathlons.

That led to half Ironman races; Dr. McKinley did eight of those.

And then in New Hampshire in 1990, he competed in the Ironman, won it and qualified for the Ironman in Hawaii.

Dr. McKinley didn’t go. He didn’t need to. He’d met his goal.

***

Inside Methodist, Dr. McKinley is known for a niche surgery that helps younger adults with hip dysplasia.

It’s a painful, nagging condition in which the hip socket is too shallow or it is oriented in the body in the wrong direction.

It’s Dr. McKinley’s specialty to fix that with an operation that restores the shape of the hip. The patient’s pain dissipates. Dr. McKinley performs 30 to 60 of those surgeries a year.

As a trauma surgeon, he’s on call five to six nights a month. At a moment’s notice, he could be in the operating room saving lives. It’s all so rewarding, he says.

“But if you ask me what keeps me up at night?” Dr. McKinley says. “It’s the research.”

Dr. McKinley is part of a research team studying precision medicine for trauma patients.

“When people think of illness, they don’t think of trauma or injury,” he says. “But trauma is a major illness.”

More life years are lost annually in the United States from trauma than cancer, stroke and heart disease combined.

“Trauma is a real disease,” he says.

So, the team is studying it as a disease.

“Five or 10 years from now, when someone comes in, we will have come up with things that not only keep them alive,” he says, “but the rest of their life will be free of pain and it will be meaningful. You can restore people’s lives and that matters.”

— By Dana Benbow, Senior Journalist at IU Health.

Reach Benbow via email dbenbow@iuhealth.org or on Twitter @danabenbow.

Growing up in Osage, McKinley’s father was an attorney and his mom stayed home with him and his two siblings.

Growing up in Osage, McKinley’s father was an attorney and his mom stayed home with him and his two siblings. While in undergrad at Minnesota, there was a triathlon in the Twin Cities. Dr. McKinley had never really swam a stroke in his life, but he decided to give the competition a try.

While in undergrad at Minnesota, there was a triathlon in the Twin Cities. Dr. McKinley had never really swam a stroke in his life, but he decided to give the competition a try.

Ginn, who is diagnosed with a form of autism, completed a workforce program through the Erskine Green Training Institute. The program, developed by The Arc of Indiana Foundation, provides opportunities for postsecondary vocational training for people with disabilities. During the three-month training, students receive both classroom and on-the-job training in food service, hospitality and healthcare support. There is no promise that a student will be hired at a company after completing training, but in Ginn’s case, there was a hospital position open, he applied and was hired to work as a patient transport. Other graduates of the training program have been hired at IU Health’s Riley Hospital for Children and IU Health North.

Ginn, who is diagnosed with a form of autism, completed a workforce program through the Erskine Green Training Institute. The program, developed by The Arc of Indiana Foundation, provides opportunities for postsecondary vocational training for people with disabilities. During the three-month training, students receive both classroom and on-the-job training in food service, hospitality and healthcare support. There is no promise that a student will be hired at a company after completing training, but in Ginn’s case, there was a hospital position open, he applied and was hired to work as a patient transport. Other graduates of the training program have been hired at IU Health’s Riley Hospital for Children and IU Health North. “They come in and are interviewed for a job, actually perform some of the tasks and are accessed on their performance before they are placed in an internship,” said Lambert. Students come from throughout Indiana and even out of state to take part in the Erskine Green Institute, said Fenway Park, a student support specialist. “We’ve even had interest from as far away as California.”

“They come in and are interviewed for a job, actually perform some of the tasks and are accessed on their performance before they are placed in an internship,” said Lambert. Students come from throughout Indiana and even out of state to take part in the Erskine Green Institute, said Fenway Park, a student support specialist. “We’ve even had interest from as far away as California.” “I knew I could do it but this gives me an opportunity to show that I can do it,” said Ginn. “I had a basic understanding of the skills needed for the job and becoming an employee makes me feel more marketable.”

“I knew I could do it but this gives me an opportunity to show that I can do it,” said Ginn. “I had a basic understanding of the skills needed for the job and becoming an employee makes me feel more marketable.”

“We were truly involved with some pioneers of the time,” says Ennis, now manager of thoracic transplant services at Methodist. “We had teams there around the clock. It was all so new and very exciting.”

“We were truly involved with some pioneers of the time,” says Ennis, now manager of thoracic transplant services at Methodist. “We had teams there around the clock. It was all so new and very exciting.”